From mouthset to mindset…

Originally published on Medium by Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation (Aug 8, 2023)

This blog is co-authored by Emma Blomkamp, Thea Snow and Ingrid Burkett

A co-design coach, a professor of systems innovation, and a public sector innovator walk into a bar. Well, maybe not a bar, but a Zoom meeting doesn’t have quite the same ring to it. In any event, three of us — Emma, Ingrid, and Thea — came together to explore synergies and differences in our work, and share our hopes and some of what we’re learning in our respective roles and fields.

We had lots of ideas to share and spoke easily and quickly. Towards the end of the conversation, we landed on a topic that piqued our collective interest:

The language of co-design and systems change is becoming so ubiquitous — everyone is either asking for it or claiming to be doing it. But what do systems and co-design approaches really ask of us? And how do we work in ways which honour this in our work?

Co-design and systems approaches are central to all of our roles — Emma builds capability in co-design, Ingrid works in systems innovation, and Thea works to reimagine government. We are all observing good and not-so-good shifts as these concepts become more mainstream.

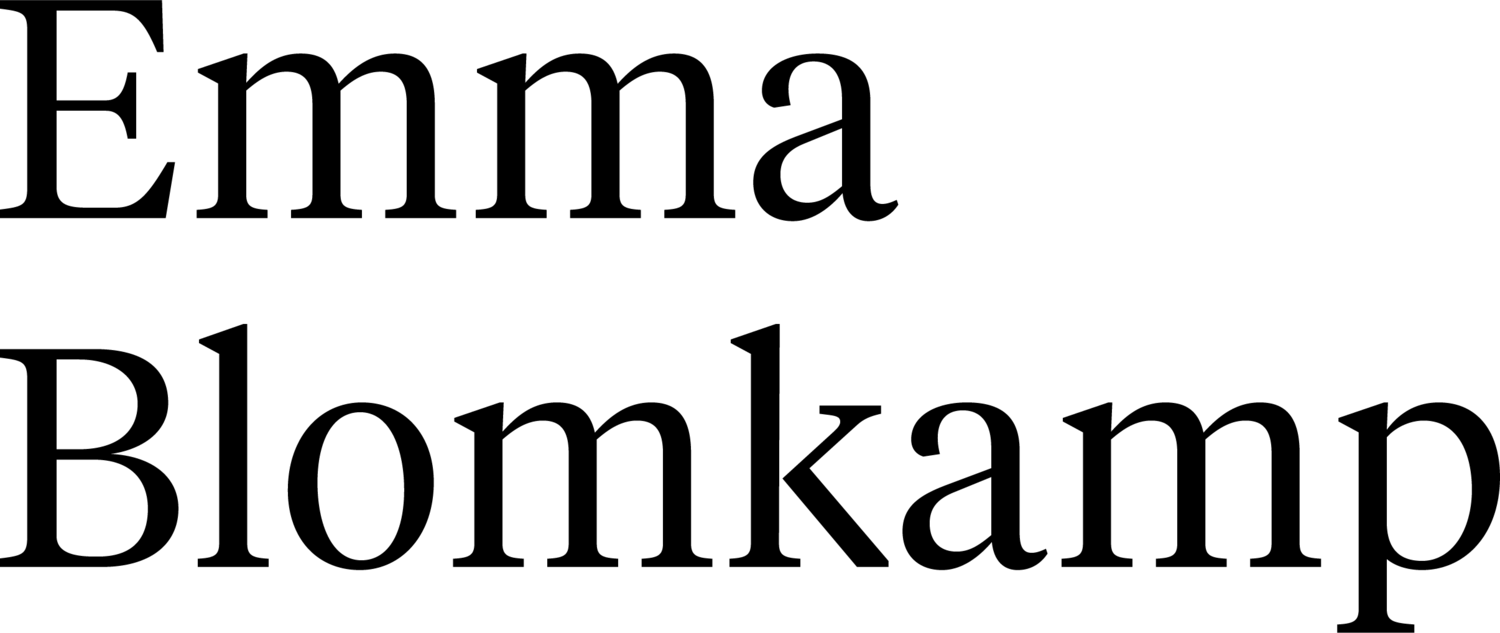

Ingrid’s framing of ‘mouthset shift to mindset shift’ encapsulates some of the frustrations and breakthroughs we’ve observed in Australia. This blog is anchored in that framework, sharing our thoughts and reflections on how the spectrum set out below is playing out in practice.

From mouthset shift to mindset shift, Ingrid Burkett, GCSI 2023

Moving from mouthset shift to mindset shift

The diagram above illustrates the three big shifts that often happen in moving from ‘mouthset’ (the adoption of the language) to the ‘mindset’ (the embedding of the language in culture, structures, and processes).

First, there is an unsettling — where feedback is provided or people in the organisation develop insights into the mismatch between words and actions. This is often brought about when powerful stakeholders offer a critique that opens a door into a sense of unease or cognitive dissonance. The key here is that the dissonance evokes a response. Not just shutting down the critique, but thoughtfully engaging with it — perhaps with a question, ‘how could we do better?’

Second, there is a breakdown. It may not be dramatic, it may be someone simply says, ‘Enough! Let’s avoid using this language if we don’t mean it’. Again, keeping on track requires holding the space where powerful stakeholders (who may not hold organisational power, but have the power to, for example, opt out of processes or ‘shame’ the organisation) amplify the critique and challenge the organisation to walk towards the critique, rather than slipping into cynicism or jumping to the next shiny concept.

And thirdly, there is a reconciling and realignment, which draws on garnering energy to do some of the really hard ‘grunt work’ of learning, practising, shifting structures, and investing in cultural shifts. This creates deeper capability and capacity to embed the concept in the values, behaviours and organising of the work. This can then lead to much deeper practice and a shift from concepts as aspirational shining lights to real, changed practice that has potential for better outcomes.

So, how is this concept expressing itself in our fields of work? Below we each reflect on our contexts to think deeply about these shifts and how we have grappled with them.

Talking the talk or walking the walk?

Firstly, let’s recognise that it’s REALLY hard to adopt new ways of working in organisations that are used to working in certain ways, within deep-rooted power structures. When concepts like ‘co-design’ or ‘systems change’ emerge, many in those organisations have great intentions and see these ideas as a way to challenge the status quo.

Sometimes the only thing that can be done inside incumbent structures is to adopt and sustain the language, hoping that it will develop into embedded practices and changed processes over time. We get that — and we’ve seen examples where that has worked — but it’s a difficult process!

So, the diagram. Let’s go back to the early, heady days of co-design. Ingrid remembers an event where an organisation gathered people with lived experience, service providers and sector leaders in a room filled with sticky notes, pens, and facilitators. At this event, attendees worked together to ‘co-design’ what they thought was a new strategy for the organisation. It was a good day, with conversation, some reasonable ideas, and a sense of having achieved something.

At the end of the day everyone got a surprise. This was actually an event — and everyone who was there was actually a guest at the launch of the organisation’s new strategy! Shiny copies of the strategy were handed out and attendees were thanked for their participation and great ideas. The room was silent. Until one brave person piped up ‘Please don’t call this co-design. You’ve just killed everything “co” about this process’.

The organisation could have been defensive — but they acknowledged that in fact co-design was their ‘aspiration’, not their reality.

Things didn’t change overnight. The organisation continued to host ‘aspirational co-design’ events, amidst a growing sense that deeper, more critical intervention was going to be needed if co-design was to become something other than theatre.

The ‘change’ was gradual. It involved continual challenging from people inside the organisation, those with lived experience, and other providers and co-design educators. There were good, strong people in that organisation who didn’t put up defences or drop co-design when they got negative feedback. Instead, they worked with it and responded and slowly shifted.

Now, things are not perfect, but this organisation is on its way to much deeper, more reflective practice. They have brought people with lived experience inside as paid workers and developed a stronger culture of co-design.

The diagram above is a representation of what happened in this organisation. It demonstrates it is possible to shift from just talking the talk of ‘co-design’ to walking the walk in the organisational mindset, culture, and way of being.

From mouthset to mindset in co-design

Co-design or faux-design is something that co-design facilitator and activist Jo Szczepanska has been asking for years, as this term has gained popularity in the social and public sectors in Australia. Szczepańska similarly approaches the ‘mouthset to mindset’ shift by encouraging us to ‘bake in co-design’ to the fabric of our organisations rather than ‘bolt on when convenient’.

‘Bolted on or baked in?’ Image by Jo Szczepanska (2023)

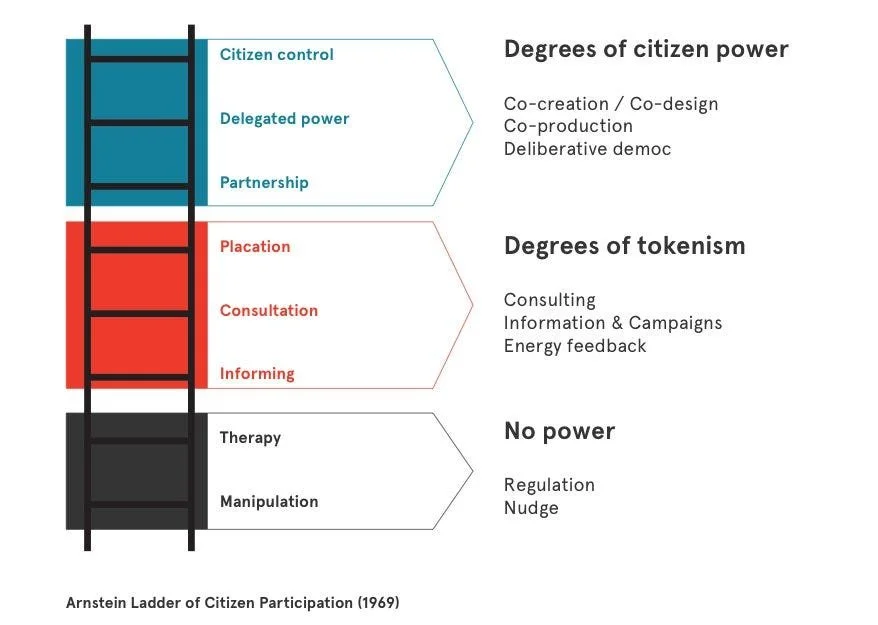

Concepts like co-design, co-production, and systems transformation can be adopted in hollow ways, co-opted, and manipulated. In 1969, warning us about ‘exacerbated rhetoric and misleading euphemisms’, Sherry Arnstein depicted this happening on the lower rungs of the ‘ladder of citizen participation’ (updated version pictured, by O’Rafferty).

This leads to a crisis of confidence in co-design, as seen when governments ask for input after big decisions have already been made. Too often they have unreasonable timeframes, even when they claim to be ‘co-designing with communities’. This dissonance happens when there has been a lack of effort to create the conditions for co-design.

As we saw in Ingrid’s example above, adding the term ‘co-design’ to an organisational plan or strategy is not enough. It’s frustrating when policies or guidelines require ‘co-design’ without providing additional funding or flexible timelines.

You can’t build more creative and participatory ways of working overnight, but change is possible. For instance, Emma has been working with an educational institution that approached her after launching a new strategic plan for teaching and learning. The plan aspires to enable meaningful education so that people grow their skills and opportunities to ‘lead prosperous and fulfilling lives’. Despite being full of words like ‘co-design’, ‘co-creation’ and ‘transformation’, it lacks details of how these practices will be implemented.

Emma and her client started with an action-learning program for the educational quality team, focused on taking a co-design approach to framing, discovery, and collaborative action. This involved sharing, modelling, and applying practical skills and tools, following common phases in a co-design process.

Trying to shift hearts, minds, and institutional practices is challenging work. Emma and the team initially faced some resistance to adopting the language of co-design, especially from staff experiencing the dissonance of having expectations to ‘co-create’ seemingly bolted onto administrative and compliance-oriented positions.

The partnership got close to a breakdown when the leader who initially sponsored this work moved on, internal friction played out, and resources ran too low to continue an organisation-wide capability-building program. After successes and failures in trialling a lighter touch coaching model and adding supplementary training workshops, the team has found a more sustainable path focused on strengthening the capability of key roles.

Throughout this partnership, the principles and mindsets for co-design have been central. Foundational concepts of systems thinking, everyday systems practices, and patterns of systems innovation are similarly good starting points to introduce fundamental tenets of these practices. These are useful guiding values to realign us, as we apply creative and participatory approaches in systems that sometimes actively resist these ways of working.

Some of the co-design leaders in this organisation had no prior experience with human-centred design or systems innovation. Two years on, they are embodying the language and principles of co-design. Their new co-designed procedure was approved and implemented, with glowing feedback from stakeholders who finally ‘felt heard’. They are now designing their own training on applying the principles of co-design at their institution, encouraging colleagues to adopt co-design mindsets without necessarily adopting the language or full process of co-design.

This is still only a small pocket of a large organisation — yet it demonstrates both the challenges and potential for moving from mouthset to mindset in co-design practice to achieve transformative outcomes.

From mouthset to mindset in government transformation initiatives

Similarly, in many government transformation initiatives, change begins slowly. In The Clock and The Cat, Mark Foden suggests that an effective way to encourage people to engage with complexity is to begin by changing the language they are using. For example, instead of “scaling” (an engineering term which connotes a linear and predictable process), he suggests using “propagation” (a term borrowed from natural systems and which implies the need to adapt based on local context).

The question, though, is how to support the language translating into deeper shifts; not just remaining at the surface level where the words act as a guise without supporting the mindset shift required to bring about transformative change.

The Centre for Public Impact (CPI) in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand is exploring how to support transformative change through a number of its learning partnerships, including a current partnership with a public sector leadership team.

Similarly to Emma’s example above, an ambitious new initiative was introduced through a Strategic Plan. But the CEO realised this new language was not enough to bring about the deep cultural shift this initiative required. They understood that to shift both hearts and minds, people had to be engaged beyond a formal document. And with this in mind, CPI was engaged to support the change process through a learning partnership with the executive leadership group and a select group of managers.

The learning partnership focussed on what Ingrid’s framework calls “realignment”. Through learning sessions, CPI ANZ worked with the cohort to:

Develop a deeper sense of connection to the initiative by defining it in their own words.

Support the development of Trojan Mice experiments — small, safe-to-fail experiments that they could take forward to support the new initiative.

Interrogate the opportunities and barriers to this initiative at different levels of the system: policies, practices, resource flows, relationships, power dynamics, and mental models.

This learning partnership was initiated because the CEO knew that a new Strategic Plan — even with a thorough roll-out — was insufficient to bring about the needed shifts. Leaders (and, arguably, every individual across the organisation) needed to develop a connection to the initiative in their own way. They also needed time and space to collectively explore the problems (dissonance/breakdown) the initiative was addressing and create a shared sense of purpose.

In CPI’s experience, this is often missing from transformation efforts. Leaders try to drive change from the top, rather than creating the space for people to explore, discover, and learn together — to experience the challenges for themselves, and co-create a pathway forward. Ingrid’s diagram illustrates that this journey is an essential driver of mindset shifts required to ensure that changes are reflected not just in words, but in individual and organisational values, behaviours, spaces, policies, and ways of working.

Inching forward in relationship

The Griffith Centre for Systems Innovation (GCSI) is working alongside government, business, and civil society bodies tackling complex issues like homelessness, place-based disadvantage, and inequity. They are working with partners who are looking to ‘shift systems’, undertake ‘systems innovation’, or apply ‘challenge-led innovation’ to help improve outcomes.

Time and again they have observed while the individuals involved are deeply committed to these shifts on a personal level — they work in organisations that have struggled to move out of the ‘business-as-usual’ approaches to addressing such issues, which mainly focus on ‘plan, act and fund a service’ or ‘build it and they will come to be changed’ approaches.

Initially, the GCSI team were confronted by these partners who adopted the terminology and the tools but couldn’t ‘change’ their deeper organisational values or practices.

Challenging themselves to meet their partners where they were at, instead of walking away the GCSI team offered deeper support. They developed trusted relationships with their partners enabling them to have robust, two-way conversations, challenge practices, ask hard questions, and share critiques.

Though a couple of clients have been lost along the way, GCSI has found new partners who wanted to be challenged and supported. This was an opportunity to develop new ways of working that could enable a deeper, relational, and transformational way of working.

Ingrid and the team created this diagram precisely because they saw how this sort of relational partnership could support a move from ‘mouthset to mindset’ over time. There’s no magic here — just a deep commitment to doing the ‘grunt’ work, reflecting on what it takes, and working in a trusting and rigorous way to move forward inch by inch towards better outcomes.

Hope and curiosity around the conditions supporting these shifts

As three authors exploring these common experiences in different settings, we are left with hope and curiosity.

The work of systems change is hard. Bringing together unlikely coalitions of people willing to be challenged and supported to create new ways of working is an awesome responsibility. Inevitably, we will face setbacks as established actors resist disruption to the status quo.

Rigid structures and inhospitable cultures will push back against our attempts to break down barriers and nurture relationships to create more compassionate systems. Opportunistic leaders will corrupt our language and inadvertently create cynicism and scepticism. Some of us will battle burnout and feelings of hopelessness.

Examples of individuals, organisations, and networks who have overcome all the barriers to change energise us. Moving through dissonance and past breakdown, we are inspired to see how they have realigned in creative and relational ways to embody the practices of transformation and innovation.

Yet we are left wondering, what conditions allow for this change, and what conditions don’t? Perhaps you share our curiosity or have some answers of your own. If you have been part of a ‘mouthset to mindset’ shift — or seen a failure — we’re keen to hear what you think. How do some groups get past surface-level adoption of the language and dissonance; while others get stuck in co-optation or breakdown? What conditions and capabilities support a shift from mouthset to mindset?