Who gets to participate in design and democracy?

Our practices and systems often privilege educated, literate extroverts, even when we call for marginalised people to participate in design processes. Around me there’s growing awareness of, and emphasis on, power-sensitive practice in social design, but we keep coming up against cultural and structural barriers. I’m curious about the limitations of participation and accountability for co-design in a representative democracy.

These were the main ideas I explored in a panel discussion on ‘The politics of design and design of politics’, as part of a seminar series celebrating 100 years of equal suffrage in Sweden. I was honoured to be invited by Stefan Holmlid to speak in September 2021 alongside participatory design legend Pelle Ehn, decolonising design visionary Tristan Schultz, perceptive public design practitioner Vanessa Rodrigues, and strategic design thought leader Dan Hill.

The full 2.5 hour webinar, hosted by Linköping University, can be viewed here.

This article is an edited version of my presentation about: who gets to design public policies and services; the limitations and potential of participation in co-design in Australia and New Zealand; and how the systems that we are part of shape our work.

To see more images I presented, please go to the version of this article published on Medium.

I focus in particular on four challenges, which I reframe as opportunities at the end of this article:

1. Reconciling fundamental differences between design and government

2. Reckoning with complicity in colonialism

3. Realising the limitations of design thinking, tools and workshops

4. The disconnect between co-design and representative democracy

Introducing my topic and positionality

One of the things that makes me proud to be a New Zealander is that we were the first country in the world where women won the right to vote — 128 years ago (on 19 September 1893). That included Indigenous women, who could vote alongside their male counterparts in Māori electorates.

Alexander and Mary McGilp stand with their children in front of the Russell Police Station, circa 1980. Source: Campbell-Hatrick family collection.

Some of my ancestors arrived in New Zealand around the same time — as pictured here in Northland in 1890. Te Tai Tokerau, the north of New Zealand, still feels like home to me, but I now live in Melbourne, Australia, on land stolen from the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation.

Of the many injustices experienced by First Nations on this continent, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples did not have full voting rights in state and federal elections until 1965.

I’m aware that the privilege I experience isn’t shared by everyone where I live. I’m particularly grateful to the suffragists, feminists, the labour movement and other change agents who fought hard for the rights I now enjoy.

I’m also aware we’re in a climate emergency and a public health crisis — and the decisions we make as societies, and the actions we take as communities, can have grave consequences.

Democracy and design, we might argue, are more important than ever.

I’m passionate about using creative and participatory methods to bring different kinds of voices and knowledge into spaces where decisions are made about the rules and resources that shape our lives.

These days I work with a lot of designers and change-makers in the public purpose sector who want to better engage people in their work to co-create more equitable and just outcomes. We follow in the footsteps of the Swedish and other Nordic forebears of participatory design, like Pelle Ehn, as well as the deep wisdom of Indigenous cultures who have been gathering, making and deciding together long before we came up with the term ‘co-design’.

The people I work with tend to be interested in how to identify and share power, and work in ways that heal rather than ways that harm. Yet many of us are also part of privileged groups working in patriarchal, colonial and neoliberal systems — and it can be extremely challenging to overcome these structural and cultural barriers and thrive in a capitalist world.

I want to highlight a few challenges I’ve noticed in this work. These are things I’ve experienced and observed as a researcher, practitioner, educator, evaluator and coach. They’re also shaped by the time I spent exploring the role of government and the significance of cultural and community wellbeing in my PhD almost a decade ago. These are some of the questions that continue to drive my work.

CHALLENGE 1: Reconciling fundamental differences between design and government

A common refrain in research on design thinking and practice in the public sector is the clash between, on one hand, linear, analytic-rational models of evidence-based policy processes, and on the other, the more creative, intuitive and experimental practices of design, founded on abductive thinking.

Image showing the journey from problem to solution, as messy back and forth in the design approach, from Leurs & Roberts’ (Nesta 2018) Playbook for Innovation Learning.

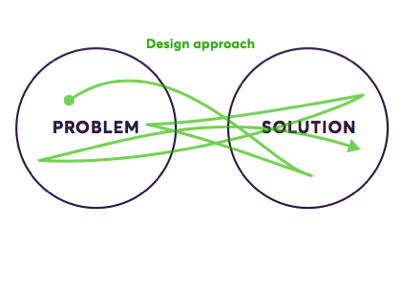

My home discipline in the academy is political sciences. Traditionally, and in many public administration courses today, political science and public management scholars have promoted the ‘policy cycle’. Yet, just like the double diamond in design, experienced practitioners and researchers know that this model is a crude simplification of messy, complicated and often compromised realities.

Problems in the conceptualisation of the policy development process as a ‘policy cycle’ — visualisation by Brookfield Institute (2018)

Interpretive policy analysts, who are at the fringes of this discipline, use abductive reasoning too. They/we see policy as a craft rather than a science, and recognise the importance of local knowledge (a similar but not identical concept to lived experience) as well as the complexity and contingency of the social and political world.

Research on design-for-policy and public innovation has similarly been highlighting the methods, techniques and tools that form part of everyday practice within the public sector. Rather than suggesting the policy process is rational or deliberative, this research helpfully draws attention to the political implications of practice as well as the particular forms of knowledge and capabilities that civil servants tend to be trained in and rewarded for.

What’s not often acknowledged is the white supremacy embedded in many of these governmental structures and professional cultures.

CHALLENGE 2: Reckoning with complicity in colonialism

Lately I’ve been reckoning with my family’s complicity and how much I personally have benefited from colonisation. Going back a few generations, my family comes from Scotland, Ireland, England, Germany, France and the Netherlands. Our social and economic situations improved as we benefited from land taken from traditional owners in South Africa, New Zealand and Australia.

I have personally benefited from the cultural capital and relative comfort I was brought up in as well as the public health and education systems that sustained and supported me growing up in New Zealand.

I learned so much from being part of a multicultural society in a bicultural nation and then later working and living in different cultures and languages to my own.

Yet I continue to be surprised by the blindspots of my whiteness that are occasionally exposed.

Early in my career, for instance, a government department commissioned the agency I worked in to educate a Māori health organisation about design for social innovation. The health workers there hadn’t asked for the training and didn’t want me there. It was so awkward. I still cringe realising how I represented the latest effort to colonise their work.

These days, I hope, I’m much more aware of my positionality and encourage my peers and clients to consider and confront their power and privilege. I try to steer clear of any ‘white saviour’ type work. Like many of my fellow practitioners, I’ve been upskilling in power-sensitive, systems-aware and trauma-informed practices, learning from disciplines and movements such as feminism, psychotherapy, decolonisation and Indigenous Knowledges.

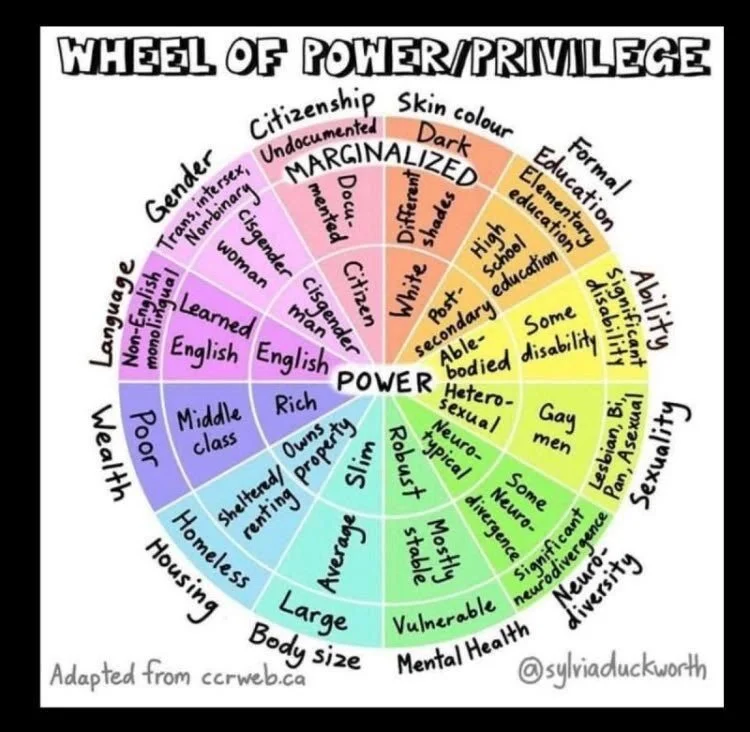

The Wheel of Power/Privilege.

Image by Sylvia Duckworth; adapted from Canadian Council of Refugees and informed by Black feminist ideas of the matrix of domination.

Even so, many of the models that we use in public design and social innovation are deeply Eurocentric and I’m learning to think more critically about the origins and rationalities of different tools and methods.

In working with diverse community members with sometimes complex needs, I’ve come to realise how exclusive some of the common tools and techniques of design thinking are. The ubiquitous sticky note assumes literacy and fluency in the dominant language. Its use in workshop settings typically requires full vision and mobility. The ability to participate in workshops assumes one has spare time, transport access, and sufficient social skills and emotional regulation.

CHALLENGE 3: Realising the limitations of design thinking, tools and workshops

It seems that the assumed participant in human-centred design projects is a literate, articulate, extrovert. Is this simply a mirror image of the ‘big ego designer’ that Ezio Manzini warned us about?

Fortunately the creative and tactile methods of design offer a much wider range of opportunities for expression. Rather than asking people to write concise thoughts on sticky notes, we can invite them to express themselves through collage, model-building, card sorting, roleplays, mapping, observation, and so on.

The challenge of moving online, especially during the pandemic, has actually created opportunities for more inclusive, flexible and accessible modes of engagement in co-design.

Diagram showing a multiplicity of co-design tools and processes, by Niki Wallace. See original in: Davis, A., et al. 2021. Low-Contact Co-Design: Considering more flexible spatiotemporal models for the co-design workshop. Strategic Design Research Journal 14:1.

The model pictured here, for instance, facilitates reflection on questions of ‘who, what, where and when’ in co-design by mapping each of these aspects in relation to time, space, people and power.

I have heard from introverts how relieved and delighted they are that we are shifting away from ‘co-design as workshop’ and towards more asynchronous and multi-choice forms of engagement. People are now less likely to be put on the spot to contribute an idea or forced to take part in some naff icebreaker that leads them to resent the whole process.

The challenge of moving online, especially during the pandemic, has actually created opportunities for more inclusive, flexible and accessible modes of engagement in co-design.

CHALLENGE 4: The disconnect between co-design and representative democracy

Something I continue to question is the role of co-design in a representative democracy. And here I have more questions than answers, but I am hopeful that bringing together theories and perspectives from different disciplines and sectors may help us to experiment and learn in this space.

I’m wondering in particular:

What is the accountability for co-design groups designing public policies and services?

We vote in politicians. Policy workers are subject to performance management regimes. Yet who are co-designers accountable to? And to what extent can we expect participants in a design process to take responsibility for their contributions?

Who gets to decide what happens in co-design?

A long-running debate I’ve been having with my friend and former colleague KA McKercher is whether co-design means co-deciding. We both agree that we need to distinguish between tokenistic forms of consultation and co-design, and that a fundamental objective of co-design is around sharing power. Yet I think we lack sophistication in our language and models of decision-making in co-design practice. I think we could learn a lot from deliberative democracy and participatory governance. But I keep coming back to the fact that we don’t live in a participatory democracy. I’m curious about the possibilities and limitations of participation and power-sharing in public design in representative democracy.

What role for elected politicians in co-design?

In particular, how do politicians fit into co-design? We often talk about privileging lived experience and valuing diverse perspectives to address the typical imbalance where narrow forms of expertise are valued most in policymaking. Yet how does this relate to the political process and electoral system? When and where is there dialogue with elected representatives? What is their role in a co-design process?

In conclusion

I’ve shared a bit about who I am, the work I do, the systems I’m part of, and the questions I’m asking.

I’ve highlighted four challenges I’ve observed from working in this space — reframed here as opportunities.

How might we…

… reconcile fundamental differences between design and government, by recognising policy as craft?

… recognise positionality, power and privilege in design practice?

… become more inclusive by using generative and asynchronous methods?

… integrate co-design practice and democratic structures and processes?

I see huge potential in the spaces where design and democracy intersect, but I know we need to keep experimenting. I encourage us to continue to have open, reflective and critical conversations about both the potential and the limitations of our methods and mindsets.